You’ve heard the adage, “You must suffer for your art,” right? Well, sometimes you must suffer for knowledge. This column began when G&A editor Eric R. Poole read a long-ago Guns & Ammo column by Col. Jeff Cooper. My predecessor commented on the marking on some new revolvers. “Not for use with bullets less than 120 grains,” he wrote. The reason? Bullet pull. Lightweight revolvers can have the last bullet in a cylinder “grow” in length, as the bullet is pulled more and more out of the case for each preceding shot.

The cause is simple: inertia. Newton’s Third Law states: “For every action, there will be an opposite and equal reaction.” When we fire a handgun, that reaction is felt recoil. When the bullet moves forward, from the moment it starts moving, it generates recoil.

If that’s the case, then why doesn’t a heavy handgun cause bullet pull the same as a light one? Velocity of the recoil. With a heavy firearm, we feel recoil as momentum. That is, mass times speed. That happens because we are much heavier than the object slamming into us, and we’re flexible. The object being accelerated is heavier than a bullet and still much lighter than we are. Our bodies give against the recoil, but our hand takes the brunt of it. Hand gets hit, arm flexes, shoulder moves a bit and the brain goes, That wasn’t too bad. A 2-pound handgun weighs 1 percent of me. However, recoil is generated as force. That’s a more complex calculation. Force, in the world of physics, is one-half the mass of the object times the square of its velocity.

Could recoil in a lightweight revolver eventually pull a bullet from an unfired cartridge in a cylinder?

In order for the force involved — bullet one way, handgun the other — to equal out, as the mass of the handgun decreases, the handgun recoil velocity must increase. But, as force, that means the increased velocity is necessarily magnified. No matter how good your lawyer is, the Law of Conservation of Energy must be obeyed.

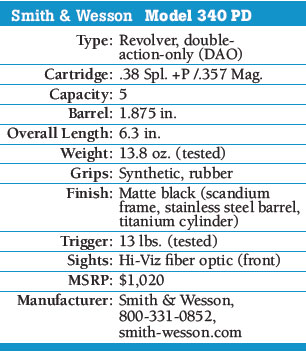

Let’s get down with a calculator and crunch some numbers. We’ll compare like to like. The standard Smith & Wesson Model 640 J-frame revolver is made of steel and weighs 22.1 ounces. The ultra-lightweight S&W 340 PD weighs 13.8 ounces. If we fire a 125-grain bullet .357 Magnum out of them, at a velocity of 1,100 feet per second (fps), the bullet generates 2.715 Newtons (N) of force. (There is a long list of units we could use, but this will do for our purposes.)

If we work the equation backward, that is, generating 2.715 N of force with either our 22.1-ounce revolver or our 13.8-ounce revolver, what do we get as the velocity for each?

The 22.1-ounce revolver comes back at us at 14.217 fps or roughly 4 ft.-lbs. The 13.8-ounce airweight? It slams back at 22.76 fps or around 7 ft.-lbs. (Ouch!) To put things in full perspective, a classic carry gun of the Mesozoic era, a 2½-inch all-steel M-19 weighing 32 ounces would have a recoil velocity of only 9.8 fps (about 3 ft.-lbs.), which is positively sedate by comparison.

The problem is not just ours. The bullets waiting their turn are also subjected to this acceleration. The revolver jolts back, and the waiting bullets — due to their inertia — attempt to remain in place. In fact, the last one up gets this jolt four times in the 340 PD before it has a chance to do its duty. It takes a lot of neck tension and crimp to keep the bullets in place when they are hammered this hard.

The problem is not just ours. The bullets waiting their turn are also subjected to this acceleration. The revolver jolts back, and the waiting bullets — due to their inertia — attempt to remain in place. In fact, the last one up gets this jolt four times in the 340 PD before it has a chance to do its duty. It takes a lot of neck tension and crimp to keep the bullets in place when they are hammered this hard.

That is why you can see “not for use with bullets less than X grains” marked on some barrels. When the ultra-lightweights started to appear, ammunition was still made for use in revolvers like that M19 and its 9.8 fps recoil velocity.

But why is the problem just with lightweight bullets? It’s due to a combination of the recoil velocity and the short bullet length. Yes, a 158-grain bullet generates more recoil, but it also has a lot more bearing surface for the case neck tension to hold onto the bullet.

Here in the 21st century, there are a lot of wispy wheelguns, and many of us carry daily. When we carry, we want something light. So, have the ammunition manufacturers kept up with the times? Or have they spent all their time and effort satisfying the needs and desires of the 9mm pistol crowd? To that end, I borrowed a S&W 340 PD and shot a cross-section of ammunition through it.

I won’t say that I tried everything. (Cut me some slack, please. Trying everything in the 340 PD would have meant pain, suffering and multiple trips to the doctor.)

Smith & Wesson Model 340 PD

When it came to test-firing, I knew this would be work, but I wasn’t prepared for just how much. One cylinder, with the last round saved for measuring, told me I needed gloves. Alas, padded recoil gloves don’t seem to exist anymore. I ended up wearing regular gloves and adding a folded strip of an old terrycloth towel between the backstrap and the palm of my hand.

I also shot both right- and left-handed, and I did my testing over a number of range sessions. I used the chronograph to determine the velocity of each load and then simply fired into the backstop, saving the last round in the cylinder as the test subject. I regularly took a break and held my shooting hand against the crusty snow on the range to ease the pain and bring down the swelling.

The ammo selected was simple: I had a cross-section of 125-grain .357 Magnum ammunition. I wanted to see if the 120-grain weight on the barrel was really the threshold.

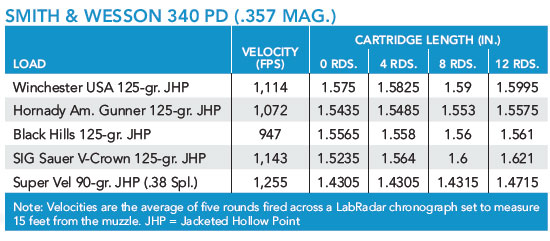

The process was simple, if brutal. I picked one round and measured it, I loaded the cylinder, shot four rounds, dumped and reloaded, and kept the old one as the last, unfired round. I subjected it to 12 rounds of its own recoil and measured its length after each of the four rounds. If there was going to be a problem, 12 rounds should show it. And if it took more than a dozen shots to create bullet pull, my hands didn’t want to know about it.

The process was simple, if brutal. I picked one round and measured it, I loaded the cylinder, shot four rounds, dumped and reloaded, and kept the old one as the last, unfired round. I subjected it to 12 rounds of its own recoil and measured its length after each of the four rounds. If there was going to be a problem, 12 rounds should show it. And if it took more than a dozen shots to create bullet pull, my hands didn’t want to know about it.

The quick and brutal answer is that you won’t have a problem for four rounds — at least not for bullet pull. There was some minimal pull, but it took eight or 12 rounds before it became a problem. Just as a cross-check, I tried the new Super Vel Super Snub .38 Special +P load in the 340 PD. For eight rounds, it held up fine. But the third cylinder pulled the bullet to a significant degree.

Even if you can stand to shoot the 340 PD with full-house .357 Magnum ammunition, the ammo will hold up better than you. You won’t have a problem with the fifth shot having lengthened too much, at least with the rounds I tested. But don’t save any unfired rounds; shoot the whole cylinder.

As for me, the S&W 340 PD loaded with +P magnums is the very meaning of the phrase “too much of a good thing.” If I’m carrying a snubbie as light as the 340 PD, it will be my backup (or third gun), and I’ll be plenty happy with the performance of a good .38 Special +P load. I had more than enough recoil in this testing. (It took a couple of days after each range trip before I could type well.) Then there’s the ferocious muzzle blast and flash that one has to contend with during each shot.

Read more: http://www.gunsandammo.com/handguns/handgunning-the-recoil-effect/#ixzz4uVK9gdub